Photography has changed the world. It has brought countries, cities, individuals closer. Perspectives and worldview changed with each new photograph shot. It reveals so much but it still not all. There are many

frames that never see the light of the day but are preserved in the imagination of the persons shooting the images. Yes, lot many are perceived but the camera never captures it. That mysterious part is preserved in the eyes of the purveyor, called photographer.

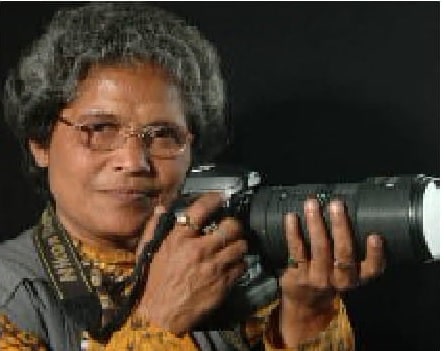

One such mystery lady is Sipra Das, whose 40 years of photo shoot has many memories etched. More than that concealed is a life of struggle, achievement, victimisation, breaking the male bastion with a gusto. As a woman, she was doubly discomfited as a newcomer does in many professions. Being a woman in an area, where still there were very few women, was a disadvantage, conflict at large that she overcame with much anguish, struggle and a continuous conflict, without succumbing to it.

Sipra is different. She can’t be cowed down. She can’t be wished away. Practical and uncompromising, she speaks with conviction and lets her photographs carry the same clarity. She has the fire like her friend

Mamata Banerjee, the fiery activist, now West Bengal’s chief minister. The resemblance between them is striking: both sharp, outspoken, and steeled by adversity. What sets them apart is not caution but audacity, a trait that has shaped and transformed their lives.

Born in the alleys of Calcutta, yes Kolkata was yet to come, she bares about her in a conversation with

Vasundhara Sinha of Just in Print.

We are bringing a tete-e-tete with Sipra. She was made to open up heart by Vasundhara with a homely

lavish meal and a touch of heart.

Vasundhara: You have a very interesting life. How did it begin? Did you ever think of being a photographer?

Sipra: It was a humble life in a locality where affluence was never heard. Everyone was struggling, so were we five siblings, three brothers and two sisters. Had to earn through my childhood to adolescence to continue my education. When in class 8 vended many items to have some earning. Also tutored 14-15 students since I was in class six. Each tuition would give me eight rupees or so. Half of the earnings were given to the family, the rest helped my schooling. A teacher, Dulalda, helped me with my examination fees.

I had a distaste for learning English but was brilliant in Mathematics and scored 99 of 100. Math needed a number of notebooks. It was a luxury and still tears roll down my eyes when I recall that a little money I had set apart for notebooks was used by a sibling without my knowledge.

I worked 14 to 15 hours a day in those years, shuttling between jobs like typing at an electrical shop and somehow squeezing in time for my studies. Most nights I would return home around midnight. Being the sole breadwinner of the family turned out to be a strange kind of blessing—it meant no one could force me into marriage.

There was a flip side. My long hours of working though supported by the family, my envious neighbours used that to malign me and assassinate character.

Having some nice clothes was not easy. My mother told me that apparels should be clean. It does not need ornamentation. Her stress was character and merit. That remains my strength.

Vasundhara: So you have been flitting from job to job?

Sipra: Every job I did taught me. For ten months worked as a drama critic, with the famous Bengali magazine Basumati, a tough job that made me study about theatre, understand theatrical nuances and

invested my evenings at some shows. Do you know after ten months was paid a “princely” sum of Rs 35.

In between, after passing BSc, with the help of multiple work assignments and help of a students’ union leader Cheena Da completed graduation. got a teacher’s job at a school college but lost it because I could not fit into a political party’s gamut.

I worked as a sound editor with All India Radio, recording talk programs that paid me just ?5 per episode. I proofread for small publications. When my features needed photographs, I would plead with photographers, but most were unhelpful. That’s when I decided to shoot my own pictures—except, I had no camera.

It was Sanjeev Mukehrjee, an agency photographer, came to my rescue. He pulled out an old, dusty Isoly-II camera, gave me a crash lesson, and told me to try. My first real assignment was the Ganga Sagar Mela. The photographs came out better than I ever imagined. That day, a new ambition was born in me—to be a

photojournalist.

Of course, the Isoly-II had its limitation. Soon realized I needed a proper camera. Sanjeev again stood by me. He found a secondhand Asahi Pentax K1000 for ?2,400 and persuaded the seller to let me pay in two instalments of ?1,200 each within three months. At that very time, AIR cleared my long-pending ?800 dues, which gave me a head start. I scraped together the rest with help from my mother. The day I held that camera in my hands, after paying the first instalment, I felt as if I had the world.

That was the turning point of my life.

Vasundhara: Was it smooth after that? Possibly you had a life you desired.

Sipra: Oh. No. Learnt life is never smooth, never simple but it guides you. You have to struggle, outdo your tormentors and new mentors emerge as well. I got into that phase. The practical world give opportunities but there are professional rivals or envious people who “help” a lot by making the road bumpy.

Vasundhara: That’s scaring. Could you narrate those moments, though may be hurting you even today?

Sipra: There are galore of it. Let me recount an experience with Satyayug, a newspaper of Jeewanlal Bandyopadhyay. Worked diligently to the satisfaction. After some months as I requested a raise of my Rs 200 stipend, he was kind enough to show me the door.

Also learnt that jobs need not come by merit. Right connections work. Lack of it can lead to missing of a deserving opportunity. I was apolitical. Got a job as I had aligned myself with Lekhak Kala Kushali Sangh. Worked as advertisement executive with Nandan magazine, later learnt it belonged to CPI-M. This landed

me at an institute as the lab demonstrator.

Vasundhara: Is not that usual? Why did not you continue there?

Sipra: Rivals are always faster than you. As they could not find fault with me. They found one. I was too skinny. They complained to the management that I should be tested for tuberculosis so that students be not at risk. Countering it was not easy. Two persons Ashis De, Director of Cottage Industry and Siben Chakravarti, Director, Small Scale Industry, helped me. Ashis De got me tested at the Calcutta’s famous Belle Vue Nursing Home. He also gave me Rs 100 to meet the cost, saying, “Lending it, return when you can”. It took three months to get the clearance from the hospital.

A CPI-M leader gave a recommendation letter. Got the job.

Vasundhara: Interesting. So how did you lose the job? How could you stray into the news photography?

Sipra: No, I did not lose the job. Told you about Sanjeev. He gave a dope. The Calcutta Municipal Corporation elections were in the offing. The Telegraph newspaper has some assignments. I shot many

photographs for them. They paid me Rs 2000. It was an opportunity to repay the rest of the instalment for my camera. Even working with the college, I got into photography assignments.

In reality, chief of bureau of The Telegraph, Tarun Ganguly, who paved the way to news photography. My male colleagues were not happy. They threw enough tantrums. Despite my fulfilment of assignments and quite often outdid my colleagues. They even did not have information. In one such case one plane crashed

near Diamond Harbour, in the south. Interestingly, my male colleagues, regular staffers, instead went to Barasat in the north. The photo clicked by me appeared on the front page causing enough commotion. One day they threw me out the film-developing laboratory.

Vasundhara: How did that happen? Why were they so vicious?

Sipra : Don’t still understand why they were so vicious. Possibly they were afraid of a woman successfully working. Or did they suffer from a fear psychosis? In fact, they often said why a woman should be in the difficult profession of news photographer. I did well. My contacts had grown and was getting many interesting photo-stories.

One such was the coverage of a flood story. The official team went in comfort by office transport. I had to travel to a distant place called Sonakhali. The police told me that quite a few streams had to be crossed by what is called vanrickshaw and boats. I was just 30 and feeling shaky to go into such an area. Still not only reached the spot, shot photos. The return was more difficult. The last bus had left Sonakhali. The locals told me to go by boat to Canning Ghat for a train. The boat with a few villagers dropped almost at midstream as because of low tide it could not sail it anymore.

It was knee to waste deep of water and slush. Got down. Found moving extremely difficult. Did not know the direction either. All of a sudden a 7-8 year-old child came. He held my hand and took me towards Canning station, quite a distance. Luckily found a local train waiting. The train should have left at 7.30 pm. It was now around 9.30 pm. It was delayed because of some local brawl. Thought it was god-sent. As

reached the train, looked for the child but he was not to be seen anywhere. He had vanished to my dismay.

At 1.30 am, reached the office and submitted the photograph. Again a page one story. And my friends

despite having gone by the car could not return.

Then Ananda Bazar Patrika having seen my work gave an appointment letter. The male photographers

created such a furore that next day the appointment letter was withdrawn. It was heart-breaking.

Vasundhara: How dare you do such difficult risky feats? Were not you afraid?

Sipra: Sure, I shook within. Could never express it or be cowed down. It’s a professional work and could never have said no once accepting it. It was traumatic, difficult but each such assignment made me more daring. The job loss is part of the reality of the profession of journalism. And the hazards are your epaulets. It also taught me that by God’s grace you get new openings.

I also got it at another Bengali newspaper AajKaal. They possibly have been watching me. There amid many stories, I managed to break an ostentatious decorated office of the fishing minister, Kiranmoy Nanda. His aquarium was talk of the town but no journalist could get a photograph. I managed to get into his office at odd hours, photographed it with his swivel chair, the rare fish and the glittering aquarium. That too was frontpaged by AajKaal.

It was one of the best of the times. For over nine months, could learn more about the intricacies of the

profession, photography tricks and connected with the people of Bengal.

Vasundhara: Indeed, I am feeling thrilled at your achievements. Envy you for surviving in such odd situations. How did you land in Press Trust of India (PTI)?

Sipra: That’s a story in itself. I did not know about it. A friend told me about the PTI vacancies in 1986. I had not applied for it. He told me that the photo editor Baby was in Calcutta for recruiting photographers. Next morning I took the plunge. Went to the Great Eastern Hotel, where he was staying. Knocked at his door. He

invited me. Asked searching questions for two hours. Saw my clippings. Offered to work for PTI, of course, as part-timer in Calcutta.

Vasundhara: Still you did not get the job? Was it easy for you now?

Sipra: For about four months, I was a part timer. During this period every month sent 72 to 90 pictures of Calcutta maidan, theatres, administration, sports and many others. The payments were good. So were the exposure.

My photos were sent to all centres. Even in Calcutta, newspapers were using my photographs. This annoyed my staff photographer friends.

Vasundhara: How did you manage now? Were you not scared that again you could lose the job?

Sipra: Certainly. The scare was there. Do you know a good worker does better when under pressure. Soon I got the opportunity.

It was a deciding moment. The then prime minister Rajiv Gandhi was to inaugurate the Farakka barrage.

Naturally, it was a plum assignment. My rivals from different papers drove to Farakka and were to go back to Calcuttta.

Me instead decided to stay at Maldah, not very far from the venue. Shot 10-12 reels. Managed to send these to PTI by the flight Rajiv Gandhi had come. Informed Delhi office. Next morning all over India, my photographs of PTI were published by newspapers countrywide. My Calcutta friends could not file their photos. Even their papers used my pictures. Let me recall those were the days when net was not there and

photograph transmission was not available.

It was a landmark achievement. Baby and G Unnikrishnan gave me my appointment letter. “You earned

your job”, both of them said in their congratulatory call. Soon I was transferred to a new domain of Delhi. That was 1989.

As usual my immediate boss Subhash Malhotra would reject whatever photo I would file. One day I picked up a picture rejected by him and put it into the editor’s file quietly. That picture got national exposure. Soon Baby told me to file my photographs to him directly. I got my recognition as also satisfaction.

Two years later India Today gave me the appointment in 1991. I am still sailing, flying and swimming through different and more difficult terrains. Still, I consider it to be a beginning of my life. It seems that small unknown Canning child, was he the God himself, holding my hands to success. I have satisfaction of photographing Yasser Arafat, Presidents Abul Kalam, Pranab Mukherjee, and array of prime ministers and

international dignitaries. The journey is on.

(She lives alone in Noida, her never say die approach guides her life, works for a publication, open for freelance assignments, her innings is far from over). Text by Shivaji Sarkar

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.